Food supply chains involve all levels of the economy. These days we hear about food supply chains in terms of obtaining imported out of season foods, but the concept also applies to maintaining food sufficiency and security.

I remember seeing a “For Better or Worse” comic strip by Lynn Johnston, where her protagonist Elly Patterson complained the local grocery store had no fresh peaches in January. Ever since then (probably 30 years ago) I have thought about our expectations about buying what we want and when we want it, regardless of season and availability.

Food supply chain problems resulting from the pandemic and accompanying delivery delays and shortages have made many people aware of the fragility of the system. In the spring of 2020, spaghetti sauce, green lentils, pasta (non-gluten free), and dishwasher pods vanished at least temporarily from my local grocery store. This year, garden seeds may be scarce (for example, dark tomatoes and strawberry bedding-out plants).

This seemed to be a good time to research the establishment of food supply chains in Canada. I began to write a blog about BC’s first big wholesale food company, Kelly, Douglas, and Company, associated with Nabob, Superstore and the Weston Food Empire. I could not get excited about it. Two Down-Easterners, Robert Kelly[i] and Frank Douglas began the company in 1896 and started their fortune by outfitting prospectors going to the Yukon Gold Rush in 1898. Unfortunately Frank Douglas drowned in 1901 (his steamer hit an iceberg) but Kelly and another Douglas brother carried on. The company-run business was enormously successful; “From Sourdough to Superstore” by Bill Davies gives a comprehensive and complete history. Robert Kelly was once called BC’s uncrowned premier for his Liberal politics and social ambitions. He may have known business inside out, but I could not visualize what insight the Kelly, Douglas story could offer about food security.

I found more relevancy in “A Cameo of the West” by Bertha Speers, the Namao Community History of Sturgeon County, first published in 1936 and revised in 1967. It has many stories of White colonial settlers who struggled with obtaining food for their families, in new surroundings. Between 1867 and 1914, the new Dominion of Canada promoted immigration. In the 19th Century, the end of the bison hunts[ii] signaled the ultimate destruction and decimation of thousands of years of First Nations and Indigenous peoples’ ways of life.

Annie Laycroft Long baked her way across the Prairies, from Winnipeg to Sturgeon County, north of Edmonton in 1881. She set out in an ox-cart with her husband George, their two-year old daughter Mary, 100 pounds of flour and a tin reflector oven. “A Cameo of the West” [iii], tells how Mrs. Long made bread every day, presumably when the ox-cart stopped for the night and a fire was available.

The trails the Longs took on their thousand-mile journey went through Brandon and North Battleford, and would have crossed many dry patches of prairie in which a local carbohydrate source, known as prairie turnip, timpsila (also spelled timpsula) or breadroot, had been cultivated and harvested by prairie First Nations peoples for thousands of years[iv].

Timpsila is a starchy tuber, growing ten centimeters (4 inches) under the soil of the Great Plains. As mentioned in a previous blog, the harvest took place every three years, and the ultimate aim was sustainability. After digging up the root, the harvesters returned the plant to the hole it came from, seed-pod down, to ensure a harvest for the next generation. The harvested roots were braided together and hung to dry for long-term storage and convenience. Then they were ground into a flour or re-hydrated in soups. According to Wikipedia[v], timpsila has a taste somewhat similar to potato and a texture softer than turnips. Wojapi, a sweet berry sauce from chokeberries or other fruit was often eaten as a carbohyrate-loaded stew.

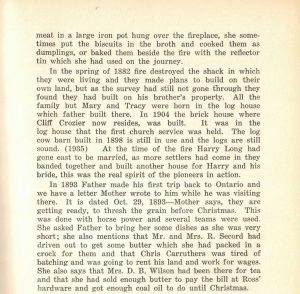

Annie Long rapidly created her own food supply chain, continuing when her family reached Sturgeon. The ox-cart had also included 20 chickens, 3 oxen, 2 cows and 2 pigs. The Little Mill on the Sturgeon had begun to mill flour in 1879 and farmers put in wheat crops as soon as they could. The following excerpts from “A Cameo of the West” show how food supply was initiated, maintained, and sustained. Mrs. Long probably was not aware of the possibilities of prairie turnips, although she would have known about the many types of berries available. Her story shows how to manage food supply systems at the micro-family level.

This blog has touched upon food supply chains from several aspects. First Nations peoples maintained the timpsila by harvesting it only every three years; Annie Long provided familiar food for her family by managing her own supplies; and the Kelly-Douglas empire made it into big business.

[i] See the Canadian Encyclopedia, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/kelly_robert_15E.html

The publication, “From Sourdough to Super Store” by Bill Davies (1990) tells the Kelly, Douglas story.

[ii] See this link for 11 extinct historic foods including the passenger pigeon and the American bison: https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/654207/extinct-foods-from-history

[iii] See “A Cameo of the West” (1935/1967) by Bertha M. Speers. The Long family history is on pages 69-71 and has been included in this blog.

[iv] Prairie turnip. https://www.seriouseats.com/2020/10/thinpsinla-the-edible-bounty-beneath-the-great-plains.html

[v] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psoralea_esculenta