Women’s Suffrage Cookbooks – Are There Any BC or Canadian Suffragist Cookbooks?

March 8, International Women’s Day is a day to recognize and celebrate women’s and girls’ social, economic, cultural, and political achievements. It is a time to reflect on the movements and organizations who worked so hard to advance women’s rights, for example. the women who lobbied for women’s right to vote.

Here in British Columbia, it wasn’t until April the 5th, 1917 that limited suffrage was granted to women. It was the fourth province in Canada to grant this. But this law still excluded British Columbians of Japanese, Chinese, and South Asian descent as well as Indigenous Canadians from the vote. Asian women and men received the vote in 1948. But it wasn’t until 1960, that all Indigenous Canadians were finally allowed to vote.

It was often common at the end of the 19th century and the early 1900s for women to use food, recipes and cookbooks to support their cause. Much has been written about two cookbooks produced in the United States:

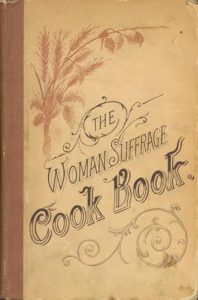

The Woman Suffrage Cookbook[i] was published in support of the movement behind the passage of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment published in Boston in 1886 edited and compiled by Hattie A. Burr. It looks like a traditional community style cookbook where the women who submitted the recipes were named. There were a few subtle references for example Rebel Soup and Election Cake. It ended with a section titled Eminent Opinions on Woman Suffrage where various quotations, and comments of famous people, academics, and so on were compiled to create an argument or rationale for women’s suffrage.

The Woman Suffrage Cookbook[i] was published in support of the movement behind the passage of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment published in Boston in 1886 edited and compiled by Hattie A. Burr. It looks like a traditional community style cookbook where the women who submitted the recipes were named. There were a few subtle references for example Rebel Soup and Election Cake. It ended with a section titled Eminent Opinions on Woman Suffrage where various quotations, and comments of famous people, academics, and so on were compiled to create an argument or rationale for women’s suffrage.

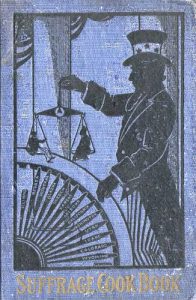

The Suffrage Cook Book[ii] first published in 1915 by The Equal Franchise Federation Of Western Pennsylvania with a cover showing Uncle Sam weighing men and women on the scales of justice, was compiled by Mrs. L. O. Kleber. It differs from the first book in that the advocacy for women’s suffrage was integrated throughout. Women submitted recipes and the recipes were categorized like a typical cookbook but sometimes the comments of the submitters was included and throughout the whole document letters from prominent figures, such as politicians, governors, academics, authors, both male and female were inserted.

The Suffrage Cook Book[ii] first published in 1915 by The Equal Franchise Federation Of Western Pennsylvania with a cover showing Uncle Sam weighing men and women on the scales of justice, was compiled by Mrs. L. O. Kleber. It differs from the first book in that the advocacy for women’s suffrage was integrated throughout. Women submitted recipes and the recipes were categorized like a typical cookbook but sometimes the comments of the submitters was included and throughout the whole document letters from prominent figures, such as politicians, governors, academics, authors, both male and female were inserted.

Various academics and journalist have examined the role of cookbooks and food related activities in women’s struggle for suffrage. They highlight various reasons for these activities. The two most obvious include fund raising funds to advance the cause, and to communicate and educate about women’s suffrage. Another reason advanced is that cookbooks showed that women’s traditional role did not conflict with suffrage. Suffragists had been attacked as unfeminine, abandoning their domestic duties and their children and families for their political beliefs and their cookbooks showed otherwise.

Journalist headlines often tell the story, for example:

- How Suffragists Used Cookbooks As A Recipe For Subversion[iii] (Nina Martryis, 2015)

- Recipes for Subversion:Women’s SuffrageCookbooks Turn 100[iv] (Diane Jacob, 2020)

- Suffragists once used cookbooks to build political power[v] (Emily Crockett, 2015)

Academics have also explored suffrage community cookbooks. Williams (2016)[vi] claims they proved that women could incorporate new practices into their lives without abandoning their traditional feminine roles. She argues that cookbooks as a cultural genres help advance certain cultural frames. She claims suffrage cookbooks allow activists to popularize a radical frame that fundamentally challenged widespread beliefs about who should have the vote.

Similarly Derleth (2018)[vii] claims that cookery rhetoric was a purposeful political tactic meant to combat perennial images of suffragists as “unwomanly women.” suffragists ultimately employed the practice and language of cookery to build a feminine persona that softened the image of their political participation and made women’s suffrage more palatable to politicians, male voters, potential activists, and the general public.

Kumin’s (2020)[viii] book All Stirred Up, linvestigated American suffrage cookbooks, reaffirming the claim that suffragists packaged their radical message in food wisdom a medium that allowed them to reach out to women in nonthreatening and accessible ways.

Kumin’s (2020)[viii] book All Stirred Up, linvestigated American suffrage cookbooks, reaffirming the claim that suffragists packaged their radical message in food wisdom a medium that allowed them to reach out to women in nonthreatening and accessible ways.

The suffrage movement was also active in Canada. Their efforts led to women gaining the vote. The first province to grant women the vote was Manitoba in 1916, followed by Alberta and Saskatchewan in the same year. British Columbia and Ontario gave women the vote in 1917, followed by the Yukon (1919), Atlantic Canada (1918-25), Québec (1940) and the NorthwestTerritories (1951). Women were granted the federal vote in 1918, marking a significant step toward Canada’s acceptance of what is now considered a universal right. However, Asian women were excluded for decades, and Indigenous women waited still longer.

My disappointment in looking at this topic, is that all the cookbook research has been carried out in the United States. So I am left with the question – were suffrage cookbooks created in Canada? A quick search of the Newman Western Canadian Cookbook Collection[ix], the Canadian Cookbook Collection[x], and Elizabeth Driver’s[xi] book yielded no results. Maybe Canadian women used other tactics to get their message out.

Does anyone have a cookbook produced by Canadian women to support the movement for women’s and universal suffrage?

[i] https://d.lib.msu.edu/fa/74#page/172/mode/2up

[ii] Https://www.gutenberg.org/files/26323/26323-h/26323-h.htm

[iii] https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/11/05/454246666/how-suffragists-used-cookbooks-as-a-recipe-for-subversion

[iv] https://diannej.com/2020/recipes-for-subversion-womens-suffrage-cookbooks-turn-100/

[v] https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/11/05/454246666/how-suffragists-used-cookbooks-as-a-recipe-for-subversion

[vi] Williams, S. J. (2016). Hiding spinach in the brownies: Frame alignment in suffrage community cookbooks, 1886–1916. Social Movement Studies, 15(2), 146-163.

[vii] Derleth, J. (2018). “Kneading Politics”: Cookery and the American Woman Suffrage Movement. The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, 17(3), 450-474

[viii] Kumin, L. (2020). All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women’s Right to Vote. Simon and Schuster.

[ix] https://ufv.arcabc.ca/islandora/object/ufv%3Acookbook?page=2

[x] https://www.lib.uoguelph.ca/archives/our-collections/culinary/canadian-cookbook-collection

[xi] Driver, E. (2008). Culinary landmarks: a bibliography of Canadian cookbooks, 1825-1949. University of Toronto Press.

Very interesting piece, I’ve skimmed it, and posted it to social media and will come back to read it more in depth. I found one v. minor typo: “Various academics and journalist[s]…” (sorry didn’t know how to report other than through comments here.)

Thanks for noticing. Typo has been fixed!