Ethel Mulvany: Changi Prisoner of War Cookbook

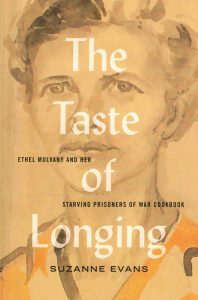

The taste of longing: Ethel Mulvany and her starving prisoners of war cookbook (2020) was written by Suzanne Evans, who holds a PhD in Religious Studies and is a former Research Fellow at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa. The Taste of Longing demonstrates how living in our imaginations can get us through tough times. Evans’ thorough research and wide-ranging sources bring her subject to life in a conversational, narrative style (1).

Ethel Rogers Mulvany had rural Ontario beginnings. She was born on Manitoulin Island in 1904 and became a teacher at age sixteen. In 1933 she managed to secure a round-the world assignment to inspect national school systems. She met and married Denis Mulvany, a British army doctor, and in 1940, they ended up in Singapore. After the December, 1941 bombing of Pearl Harbour, the Japanese Imperial Army moved quickly into South East Asia, including Singapore.

When the internment order for all non-residents of Singapore came in March of 1942, Mulvany had only enough time to grab a few possessions, including her 1932 copy of A Guide to Good Cooking compiled by Five Roses Flour. She and Denis, and 3,500 other enemy aliens were marched under armed guard to Changi Prison, 14 kilometers from Singapore, built to hold 600 people. Men and women were housed separately and after awhile the men took over the cooking. Extreme physical strength was required, including keeping wood fires going and hefting heavy pots. For the next three and a half years, all of the internees were deprived, desolated and near-starved, as described by Evans.

This left the women to discuss and dream about food constantly. Mulvany became the procurer of all supplies by virtue of her position as the Red Cross Representative at Changi, dealing in the black market and selling items for her fellow internees. Given the POW population of British, American, Australian, New Zealand, Canadian and a few Northern Europeans, British recipes dominated. Life at Changi required keeping up appearances, even if the internees were starving. The women put on imaginary teas in which they set tables according to etiquette including fantasy centerpieces. The Five Roses Cookbook food illustrations were popular viewing.

According to Evans’ research interviews, the women discussed recipes for many months before agreeing how certain food items should be prepared, and then writing them out on strips of newspaper margins. Eventually, several hundred recipes were collected and copied over into two ledgers.

Mulvany, with a past history of mental illness, frequently did not fare as well as others in the camp. Still she managed to take the ledgers with her when Changi was finally liberated in September of 1945. A year later she convinced a publisher to print 20,000 copies of a cookbook entitled The Prisoners of War Cook Book : This is a Collection of Recipes made by Starving Prisoners of War When They were Interned in Changi Jail, Singapore. Sales of the Cook Book raised $18,000 to send food to former POWs hospitalized in England.

After the war, Mulvany and her husband were divorced, and the remainder of her long life was spent in various helping capacities. For example, she started Treasure Van, sponsored by World University Service (WUS) that brought the first inklings of fair trade to university campuses across Canada. She spent her last years on Manitoulin Island, and many of her papers and taped interviews are held at the Pioneer Museum at Mindemoya. Reprints of the original Prisoners of War Cook Book have been available at the museum.

The Taste of Longing is well worth reading for understanding how a collection of recipes can serve as diaries, memoirs, and openings to an obscured past. The following recipe appears in Evans’ book. It includes fairly exact directions, and it includes a political statement about the type of peppermint to use. It’s easy to imagine the woman who wrote out the recipe; in a state of severe malnutrition and/or semi-starvation, and for a short while, escaping reality through imagining a mint type of candy.

The Taste of Longing is well worth reading for understanding how a collection of recipes can serve as diaries, memoirs, and openings to an obscured past. The following recipe appears in Evans’ book. It includes fairly exact directions, and it includes a political statement about the type of peppermint to use. It’s easy to imagine the woman who wrote out the recipe; in a state of severe malnutrition and/or semi-starvation, and for a short while, escaping reality through imagining a mint type of candy.

References:

(1). See the following article by Suzanne Evans for an academic analysis of internee cookbooks:

Evans, S. (2013). Culinary imagination as a survival tool: Ethel Mulvany and the Changi Jail prisoners of war cookbook, Singapore, 1942-1945. Canadian Military History, 22 (1), 39-49.

Book Reference:

Evans, S. (2020). The Taste of Longing: Ethel Mulvany and her starving prisoners of war cookbook. Between the Lines: Toronto. 335 pages (includes substantial notes and contributors, including recipe testers). ISBN 9781771134897