Ulu – Women’s Knife

Note* This post was compiled from previous writing by Dr. Marlene Atleo and Dr. Mary Gale Smith

Cutting foods appropriately has long been a skill that women are expected to achieve. In Germany it used to be a hallmark of womanhood if she could cut rye bread straight and thin. In most indigenous cultures, knife skills are valued particularly in coming of age ceremonies for girls.

The issues of specialty equipment and sustainability need to be examined. Do we need specialty items? Or can we adapt tools to reduce physical stress by ourselves? And are there tools for women that might be differently adapted than for men, based on biomechanics? (And safety for left-handed people).

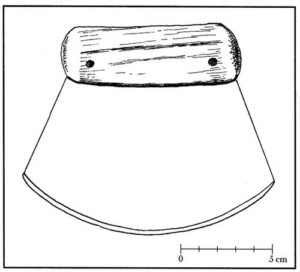

The ulu knife is often called a “women’s knife”. Evidence of the ulu has been linked to the Viking era in Scandinavia and Europe and to many indigenous cultures pre-contact.

The unique design of the ulu knife ensures that the force is centered more over the middle of the blade than typical in an ordinary knife. This creates twice the direct downward force of ordinary knives. The ingenious ergonomic design makes slicing, chopping and other uses more comfortable.

Ulus were created in many sizes, small ones for young girls to imitate their elders, small and medium sizes for cutting hair, clothing construction (a forerunner of the rotary cutter?) and fine cutting, and large ones for large fish and butchering meat sources.

We live in an era where the “chef’s knife” is often the prized tool in the kitchen. It is time to question the tools and technology used and promoted in Home Economics (Human Ecology/Family Studies/Family and Consumer Science).

Have we explored with students the social, historical, cultural heritage and significance of the tools used? Why in a home-economics dominated field, are most of us not familiar with the “women’s knife”?

What has contributed to its loss? (Colonialism? Corporate capitalism? Patriarchy? Cultural Genocide?). Losses like this may generate culinary and other cultural consequences too deep to immediately fathom.

Note: Thanks to Dr. Marlene Atleo for the original paper in the 13th Annual Canadian Home Economics Education Symposium, Dr. Mary Gale Smith for writing the commentary, and Martina Seo for announcing she had won an ulu from the Inuvik Tourism Association, spurring this post. (Photo contributed).

2015 – Canadian HE Symposium proceedings

References

Briggs, J. L. (1991). Expecting the unexpected: Canadian Inuit training for an experimental lifestyle. Ethos, 19 (3), 259–287. http://www.jstor.org/stable/640523

Dawson, P., Levy, R., & Lyons, N. (2011). ‘Breaking the fourth wall’: 3D virtual worlds as tools for knowledge repatriation in archaeology. Journal of Social Archaeology, 11(3), 387-402. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469605311417064

Frink, L., Hoffman, B. & Shaw, R. (2003). Ulu knife use in Western Alaska: A comparative ethnoarchaeological study. Current Anthropology, 44 (1), 116-122. https://doi.org/10.1086/345688

Mom Prepares (2014). The 9 best knives for the homesteading woman. Retrieved from: http://momprepares.com/best-knives-for-women/

Turner, N. J., R. Gregory, C. Brooks, L. Failing, and T. Satterfield. 2008. From invisibility to transparency: identifying the implications. Ecology and Society, 13(2), 7. [online] URL: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss2/art7/

Ulu Factory (2014). History of the ulu. Retrieved from

https://theulufactory.com/ulu-history.php