Reader’s Choice” – An Example of the Historical Significance of Sharing Recipes

Contributed by Gale Smith

From the 1930s to the 1980s, the Vancouver Sun published “reader’s choice” recipes in the “women’s pages”. These recipes were compiled yearly into cook books titled Reader Choice Prizing Winning Recipes. These recipes are a form of community cookbook in the sense that they served a larger community, the women who lived in British Columbia at the time, and they are similar to community cookbooks in that they are a compilation of recipes submitted by members (generally women) of the community willingly shared for a specific purpose. The recipes I have chosen are the ones that slipped out of my grandmother’s cookbook.

My paternal grandmother died in 1964. Shortly after she died a crate of items from her home arrived at our home. When we opened it, the item that I claimed was the American Women’s Cook Book published in 1946. I never paid much attention to it but it stayed with me all the years through many moves. Recently I opened and examined it more closely. The cookbook itself showed little use. No pages with food splashes. No dog-eared pages. In fact the book seemed to have been used more as a filing cabinet for newspaper articles, old letters and fact sheets on gardening. In looking more closely, I noticed that many of the newspaper clippings were from The Vancouver Sun’s women’s pages under the heading Readers’ Prize Recipe. These recipes were sent in by readers and if selected for publication the reader received a prize of one dollar.

My grandmother lived in a small community in northwestern British Columbia. Of the four Reader’s Prize Recipes I have selected for review, two were from the lower mainland, one from Campbell River and the other from Trail. The prize contest thus provided the opportunity for women to share their recipes and cooking ideas with a larger community of women. Also for my grandmother (and probably others) it offered a chance to connect with homeland, roots, and heritage. She immigrated from above the Arctic Circle in Norway to Seattle and eventually to northwestern BC where she settled and became a successful business woman. She never returned to her country. One of the recipes she clipped out was the Norwegian Frystekake. Perhaps it provided a taste of home. The recipes follow a standard format indicating that they may have been modified slightly from the original but they all assume that women of the time had domestic knowledge and were familiar with cooking and that some baking equipment (e.g., mixing bowls, standard measures, mixing spoons, baking pans) were standard equipment in most home. For example, in the Macaroon Brownies the first direction is “cream butter, add sugar and cream until light and fluffy”. In today’s they would more likely be written – “beat butter with an electric mixer in a large mixing bowl on medium speed for… minutes.” The Irish Oatcakes say “bake in a moderate oven” but does not give an exact temperature. This may indicate that the submitter used a wood or wood and coal stove without a calibrated oven, or that most women cooked and would know what “moderate oven” was. Of the four submitters, only one used her own name, Mrs. Gladys Hawes. The rest used initials that were presumably their husbands, an indication of the patriarchal nature of marriage at the time. It makes one wonder whether Gladys was widowed or just ahead of her time. In our current era of concern about privacy, security, and identity theft in a society increasingly subjected to various forms of surveillance and social control, it is interesting that home addresses including street and house number was given were given for three of the pictured recipes. Mrs. W. H. Smith of Campbell River gave her postal box address.

original but they all assume that women of the time had domestic knowledge and were familiar with cooking and that some baking equipment (e.g., mixing bowls, standard measures, mixing spoons, baking pans) were standard equipment in most home. For example, in the Macaroon Brownies the first direction is “cream butter, add sugar and cream until light and fluffy”. In today’s they would more likely be written – “beat butter with an electric mixer in a large mixing bowl on medium speed for… minutes.” The Irish Oatcakes say “bake in a moderate oven” but does not give an exact temperature. This may indicate that the submitter used a wood or wood and coal stove without a calibrated oven, or that most women cooked and would know what “moderate oven” was. Of the four submitters, only one used her own name, Mrs. Gladys Hawes. The rest used initials that were presumably their husbands, an indication of the patriarchal nature of marriage at the time. It makes one wonder whether Gladys was widowed or just ahead of her time. In our current era of concern about privacy, security, and identity theft in a society increasingly subjected to various forms of surveillance and social control, it is interesting that home addresses including street and house number was given were given for three of the pictured recipes. Mrs. W. H. Smith of Campbell River gave her postal box address.

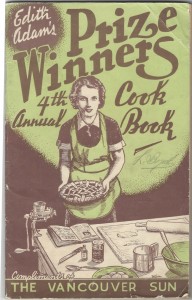

This speaks to a kinder, safer society where neighbours trusted and relied on one another and where connection and community were common values. To enhance the sense of connection each of the Reader’s Prize Recipes contained a comment from the submitter. “These cookies are liked by young and old” writes Mrs. W. H. Smith about her Choco-Oat Cookies. Mrs. Gladys Hawes, says “This is a rich confection” of her Norwegian Frystekake. “Don’t brown the cakes as this makes them taste bitter” warns Mrs. W. R. Patey about the Irish Oat Cakes, demonstrating that knowledge is created in the hestian domain that informs problems related to nurturing and sustenance. Mrs. G. M. Schmidt comments “If these should win me the prize, would you please send me the three Edith Adams’ cook books which are advertised at the special price of one dollar?”

The reference is to the cookbooks of compiled Readers’ Prize Recipes.  In italics at the end of each recipe were advertisements for other publications prepared by the fictional Edith Adams, such as: “Tough cuts of meat can be tenderized quickly in your pressure cooker. Send for Edith Adams’ Cooking Under Pressure (37 cents) and enjoy easily followed directions for the modern pressure utensil.” This “modern pressure utensil” was the commercial saucepan-style pressure cooker designed for home use that debuted at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. After the war the consumer pressure-cooker market took off. It revolutionized how the average homemaker was able to cook. The benefits of using a pressure cooker for preparing meals in just one-third of the time was perhaps the beginning of the trend to greater convenience in food preparation and food products.

In italics at the end of each recipe were advertisements for other publications prepared by the fictional Edith Adams, such as: “Tough cuts of meat can be tenderized quickly in your pressure cooker. Send for Edith Adams’ Cooking Under Pressure (37 cents) and enjoy easily followed directions for the modern pressure utensil.” This “modern pressure utensil” was the commercial saucepan-style pressure cooker designed for home use that debuted at the New York World’s Fair in 1939. After the war the consumer pressure-cooker market took off. It revolutionized how the average homemaker was able to cook. The benefits of using a pressure cooker for preparing meals in just one-third of the time was perhaps the beginning of the trend to greater convenience in food preparation and food products.

Each year from the 1930’s to 1950’s the winning recipes were compiled into Edith Adam’s Prize Winners Annual Cook Book and described as “readers’ tested recipes” and “basic cookery”. Edith Adams was fictional food editor of the women’s pages of The Vancouver Sun from 1924 to 1999. There were a number of Edith Adams over the years, many of them with a background in home economics and a home economics degree. These books have the same purposes that Bower (1997) proposes for community cookbooks: presenting women as professionals of domestic work; food as an cultural artifact; and bringing to the public the voice of people typically denied a space. Edith Adams recipe collections were reputed to be especially reliable (Driver, 2008) perhaps because they were practical recipes, connected to “real” people and made in “real” homes where preparing food for families was a “real” event.

In 2005, Whitecap Books set out to publish a compilation of the annual Edith Adams prize cookbooks. Whitecap sent out a clarion call to anyone possessing old copies of the stapled cookbooks and the result was a compilation of 13 years of the prize cookbooks in a publication called Edith Adams Omnibus – testimony to the historical and social significance of Readers’ Prize Recipes, as repositories of domestic knowledge and technology.

References:

Bower, A. (1997). Recipes for Reading: Community Cookbooks, Stories and Histories. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press.

Driver, E. (2008). Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825-1949. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.