Hogan’s Alley- Vie’s Chicken and Steak House

Celebrating Black History Month, and written by Dr. Mary Gale Smith for BC Food History Network.

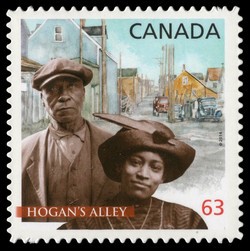

In January 2014 in honour of Black History month Canada Post issued a commemorative stamp celebrating Hogan’s Alley in Vancouver’s Strathcona neighbourhood. [i]

If you live in Vancouver, you may be familiar with the initiative to restore Hogan’s Alley, the unofficial name for Park Lane. The alley ran between Union and Prior Streets from approximately Main Street to Jackson Avenue. It was home to Vancouver’s Black population and a vibrant destination for food and jazz.

The western half of Hogan’s Alley was destroyed when the Vancouver city council of the time made the decision to demolish it in order to build the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts in the 1960s and 70s. The demolition was part of a wave of “urban renewal” efforts across Canada and the United States that often targeted Black communities and cultural enclaves[ii]. They were examples of cities catering to the car culture with the goal in Vancouver to construct a freeway through the city. The freeway was never completed but the construction of the viaducts essentially destroyed the centre of Strathcona’s Black neighbourhood and parts of Chinatown[iii].

Then forty-five years later, in 2015, Vancouver City Council voted to approve a revised roadmap that would eventually lead to the removal of the Georgia and Dunsmuir viaducts. Members of the Black community came together to demand redress and to ask the City to engage with them in planning the area, and devote resources to a Black cultural center, social housing, and space for Black-owned businesses.[iv]

Of all the Black cultural institutions in the original Hogan’s Alley neighbourhood, the most iconic are the “chicken house” restaurants, which often doubled as speakeasies. The most frequently mentioned and longest-running of these Southern- style chicken joints was Vie’s Chicken and Steak House[v]. Being on the edge of Hogan’s Alley at 209 Union Street, it survived the destruction and operated for 31 years in a house that has since been torn down.

Vie’s Chicken and Steak House was operated by Viva (Vie) and Bob Moore. Open from late afternoon (5 to 6 o’clock depending on the source) until the wee hours of the morning (4 or 5 a.m.), it was a favourite of the neighbourhood and a popular haunt for touring entertainers (e.g., Lena Horne, Sammy Davis Jr, Louis Armstrong, Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Lou Rawls, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Diana Ross and the Supremes, and Jimi Hendrix, whose mother was a cook there) and late-night workers (taxi drivers, police, newspaper reporters, fishermen, loggers, etc.). The late-night diner was the bottom floor of a small two story house. It was colourful in décor with yellow and blue walls with a red ceiling, oil-cloth-covered mismatched tables and folding chairs, with a jukebox in the corner and a painting of the Alaska Highway on the wall.[vi].

Vie’s Chicken and Steak house was true to its name with only chicken and steak on the menu. The steaks were pan-fried in huge cast iron frying pans on a black, oil-fired stove that threw so much heat it warmed the three-room restaurant even in the coldest weather. Vie was famous for never burning a steak. They were cooked “home style” fried with a little butter and garlic, salt and pepper.

I couldn’t find much on how the chicken was prepared but a September 1963 article in the Vancouver Sun said “She put some rub on it and put it in the oven”[vii] and it was described as very moist. Accompaniments were simple – fresh biscuits for sure, and salad, green peas, raw Spanish onions marinated in oil and vinegar, or garlic fried mushrooms and fries (depending on the source).[viii] And that’s it. It could be described as a “bottle club” as Vie’s did not sell liquor but you were welcome to bring your own.

When Vie died in 1975, her daughter, Adelene Ellen Alexander Clark, known affectionately as “Ma” took over until the restaurant closed in 1979.[ix]  Bertha Clark beside a memorial plate commemorating Vie’s Chicken and Steak House operated by her grandmother Viva Moore and mother Adelene Clark[x].

Bertha Clark beside a memorial plate commemorating Vie’s Chicken and Steak House operated by her grandmother Viva Moore and mother Adelene Clark[x].

Vie was born on Saltspring Island, from a pioneering B.C. family who were descendants of free blacks from California.[xi]. This brings us to another little known bit of BC history.

In 1858, free Blacks who had ended up in California from various parts of the United States became increasingly concerned about the discriminatory racist laws that were being enacted and feared for their safety. They began to explore possible safe havens to settle in and delegations were sent out from San Francisco to look for prospective places[xii]. One group came to the Colony of Vancouver Island. They met with Governor James Douglas to find out how they would be received. The Governor, the son of a Scottish father and free West Indian mother, told them they would be welcome and fairly treated. The colony had abolished slavery. They could purchase and pre-empt land, their children could go to school. After seven years they could become a British citizen by taking an oath of allegiance, giving them the right to vote, sit as a juror, and be treated equally under British law. While the British colonies of the Pacific Northwest were overrun with migrants from all lands on the quest for gold, this black community sought freedom and political enfranchisement as much as fortune. So by the spring of 1859, 400 to 600 (depending on the source) Blacks had landed in Victoria.[xiii]

The Victoria experience was not rosy as it sounded. Vancouver Island failed to be the expected haven from discrimination and racism. In fact Pilton (1951) asserts that some actually felt they experienced more prejudice here than in the United States.[xiv] Some families decided to move to Salt Spring Island. They had hopes of establishing their own colony there but Douglas refused to allow that, favouring instead a mixed settlement. However by 1866 about fifteen Black families had settled at various locations on Salt Spring along with other pioneers from other countries and those who had given up on the Cariboo gold rush.[xv] Although all the settlers were farmers/ranchers and often had to rely on each other to survive, there were still problems, hostility with white neighbours and raids by First Nations. In the space of two years, three Black men were killed. Land owner William Robinson’s murder in 1868 received the most attention as an Indigenous man named Tshuanhussetwas tried and hanged for the crime, a charge that even today is questioned.[xvi]

The American Civil War ended in 1865, and the process of rebuilding a united country free of slavery was taking place, making a return to the United States possible. It is not known which of these conditions accounted for many Black families leaving the island but the population slowly declined.[xvii] Although many returned to the United States and a few stayed on Salt Spring Island,[xviii] the British Columbian Black population began to cluster in Vancouver as the city became the economic center of the province. They settled in the East Side neighbourhood of Strathcona creating a lively and unique community where eateries such as Vie’s Chicken and Steak House could thrive as cultural hubs and a part of BC’s rich food history.

Endnotes

[i] Griffin, K. (2019, Sept. 27). This week in history 1979. Vancouver Sun, https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/this-week-in-history-1979-at-vies-everyone-got-equal-treatment-and-great-food

[ii] Watch the YouTube video Return to Hogan’s Alley for further background. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B-8lgpvj0Hg

[iii] Scott, C. (2013, Aug. 12). The End of Hogan’s Alley – Part 1, Spacing Vancouver http://spacing.ca/vancouver/2013/08/12/the-end-of-hogans-alley-part-1/

[iv] https://www.hogansalleysociety.org/ Is “revitalizing” Hogan’s Alley Black racial justice? Tensions between real estate and redress in Black Vancouver’s community and housing development, an interview with Lama Mugabo May 21, 2019, http://thevolcano.org/

[v] Watch the UTube video on Vie’s Chicken and Steak house https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_khoX5h2FkQ

[vi] https://www.laughinghand.com/vieschickenandsteakhousestory.html; Griffin, K. (2019, Sept. 27).

[vii] Vie’s Chicken and steak house, 209 Union Street, Vancouver Sun, April 16, 2011. https://www.pressreader.com/canada/vancouver-sun/20110416/293329087733153

[viii] https://www.laughinghand.com/vieschickenandsteakhousestory.html; https://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/this-week-in-history-1979-at-vies-everyone-got-equal-treatment-and-great-food

[ix] McMartin, P. (1999, January 9). Ma’s Sprawling Family Draws Together to Commemorate a Remarkable Woman. Vancouver Sun, A3.

[x] https://www.dreamstime.com/editorial-photo-bertha-clark-black-strathcona-plate-commemorating-her-grandma-owner-vies-chicken-steaks-favorite-destination-image47027996

[xi]Griffin, K. (2019, Sept. 27). [see above].

[xii] Edwards, M. (1977).The War of Complexional Distinction: Blacks in Gold Rush California & British Columbia. California Historical Quarterly (1977) 56 (1): 34–45. https://doi.org/10.2307/25157682

[xiii] Kilian, C. (1978). Go do some great thing: The black pioneers of British Columbia. Douglas & McIntyre; Wong, M. (2020, June 12). Black Colonists: The First Non-British Settlers, The Orca, https://theorca.ca/visiting-pod/black-colonists-the-first-non-british-settlers/

[xiv] Pilton, J. W. (1951). Negro Settlement in British Columbia. University of British Columbia, unpublished master’s thesis, 4.

[xv] Irby, C. (1974). The Black Settlers on Saltspring Island in the Nineteenth Century. Phylon, Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers 35(4), 368-374. DOI: 10.2307/274740

[xvi] Singleton, J. (n.d.) Mystery of Salt Spring Island: Who Killed Canada’s Black Landowners? Black Agenda Report. https://www.blackagendareport.com/content/mystery-salt-spring-island-who-killed-canada%E2%80%99s-black-landowners

Lutz, J. & Sandwell, R. (1997). Who Killed William Robinson? Race, Justice and Settling the Land: A Historical Whodunnit. https://www.canadianmysteries.ca/sites/robinson/home/indexen.html

[xvii] Sandwell, R. W. (1997). Reading the land: rural discourse and the practice of settlement, Salt Spring Island, British Columbia, 1859-1891 (Doctoral dissertation, Theses (Dept. of History)/Simon Fraser University).

[xviii] Bealy, J. (2008). Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone: A Photo Narrative Of Black Heritage On Salt Spring Island. Dancing Crow Press.