Food Security in 1860s British Columbia

Lately I have been reading the Cariboo Sentinel newspaper from the late 1860s (https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/bcnewspapers/xcariboosen)[i] searching for information on a few historic characters I am researching. At the same time I have been drawn to articles about food of the time.

From the mid 1860s up to 1871 was an exciting time in the Colony of British Columbia. There was much debate about the future of the Colony and many views on whether it should remain independent, join the United States, or the Dominion of Canada. In 1868, elected representatives from throughout BC met at the Yale Convention to decide on terms for entry into the Dominion. In 1858, thousands of people had streamed into BC as part of the Fraser River gold rush and considerable excitement remained over the next few years. The “gold rush” advanced up the Fraser River and into the Cariboo region by 1861-62. The Cariboo Wagon Road up the Fraser Canyon and over to Barkerville was completed in 1865 but resulted in considerable debt for the Colony. And, the population according to the 1871 census was only 4,628 with most people living in the coastal areas.[ii]

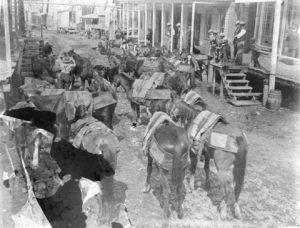

The initial rush of people in search of gold in BC preceded an adequate food supply. People had to bring their food with them, live on the native plants and wildlife, or purchase from indigenous people. Entrepreneurs quickly sprang into action to bring food and mining supplies into the main distribution points of Victoria, Port Douglas and Yale from which pack trains carried it into the interior. By the late 1860s the population in the Cariboo had dwindled from its peak, the most gold-promising areas had been staked, the gold had to be mined rather than panned, and only the serious miners remained. With the completion of the Cariboo Wagon Road, roadhouses were established every 15 miles or so and they provided meals and accommodation for travellers. The most popular houses were those that could provide fresh produce and meat for guests. This meant that farms and ranches became attached to some roadhouses and other farmers began to produce milk, butter, and grains for miners and settlers in villages and towns.

The late 1860s became a time of transition from importing foods into BC to experimenting with growing foods locally and even exporting. The Cariboo Sentinel provides a glimpse at the beginnings of local production and those beginnings resonate with the foods that have been most in demand during our current time of Covid-19.

In 1869 a supply of flour for the Cariboo was a problem. The people had relied on flour from Oregon but Oregon had experienced a drought and it was feared that flour would be very costly if it had to be sourced internationally. Fortunately, “Messrs. Harper Bros. alone have about 100 tons of wheat at Clinton, which they intend converting into flour to be forwarded to Williams Creek.” In September of that year, the news reported that the flour had been milled, that the bakers in town deemed the quality to be “excellent”, and that the large storehouse just completed by the Harper Bros. would hold sufficient flour to prevent a scarcity during the winter.[iii]

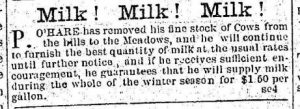

In addition to growing wheat, farmers were establishing dairies to supply milk and butter to people of the area.

Agriculture reports were sometimes mixed in with “Mining Intelligence” reports. For example: “On Moorhead Creek: D. Disher has a goat ranch under way and it is likely to pay well. The animals require very little care and furnish excellent meat and milk to the miners.” [iv] Another mining report included a note that one of the miners had grown a radish that measured seven inches in diameter.

Size and quality of vegetables were worthy of reporting because they implied that the soils and climate were excellent for farming and gardening. “A cauliflower weighing twenty-six pounds, grown on the Fraser flats by Mr. W.H. Ladner is the latest agricultural novelty.”[v]

Foods grown in other parts of the Colony mattered because entrepreneurs were transporting foods from the coastal areas to the interior. In 1867 the newspaper reported that F.J. Barnard, creator of the BX Express and Stage Line that ran from Yale to Barkerville, was having a cellar excavated out of solid rock at the rear of his Express office (in Barkerville) in which he planned “to preserve fruit for winter use”. He had purchased all the apples and pears in McRoberts’ Orchard in the Lower Fraser.[vi] Farmers at Lillooet were producing onions “of the best quality and in splendid condition for sale cheap” at B. Edwards’ Store in Barkerville.[vii] Another reported “Some tomatoes and corn were brought to Barkerville yesterday. The tomatoes sold readily at $1 per pound.”[viii]

The newspaper also reported on wild fruit in the area commenting that a miner from Grouse Creek had brought in samples of three different currants grown in the area. “One is the wild black currant which grows abundantly almost everywhere in the Cariboo and is distinguishable by the blue grape-coloured mold which covers it; another is the regular black currant of the same species as are grown in gardens; the other sample is a red currant almost as large as the best variety of garden currants.” Wild fruits were particularly abundant this year and this was attributable to the cutting of the dense forest that allowed the smaller shrubs to grow. It was also noted that raspberries were abundant as were wild cherries although the cherries were extremely small.[ix]

The salmon run in 1869 was reported as being “extraordinarily large” in the Thompson and Fraser Rivers, and many of the creeks. Both the miners and indigenous people were taking advantage of the large run and drying the fish for winter use although the preservation method used by one miner is unclear. It was reported: “Four men are taking salmon at Bear Lake, where there is a large quantity and putting them in barrels for winter use. A miner on Antler Creek is said to have sluice-forked 400 lbs of salmon in sluice boxes and sold the fish at 25 cents per pound.”[x]

Prior to and during the early years of the gold rush, fresh meat was mainly secured through hunting. Most adventurers packed bacon and beans, bacon and tea were considered staples. When thousands arrived in the Colony of British Columbia during the early gold rush years the demand for beef coincided with a surplus in California and Oregon. The enterprising Harper Bros were involved once again, mainly Jerome Harper who drove cattle from California annually for most of the gold rush years. Four to six hundred head of cattle in a drive was common and each year, thousands would cross the border at Osoyoos heading for mining camps in British Columbia.[xi] By 1869, sheep and cattle were being raised locally in sufficient numbers that farmers and ranchers were soon seeking export markets.

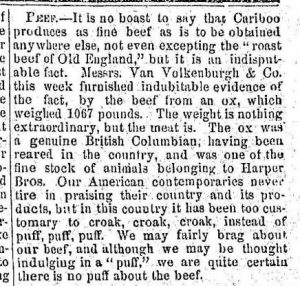

The quality of local meat was a testament to the agricultural potential of the area. One report claimed: “The grasses of the Cariboo mountains are certainly not excelled by those of any other country for feeding cattle and sheep. Neither do they thin out or disappear as is the case with the bunchgrass of the interior. … Yesterday some of Messrs. Van Volkenburg & Co.’s lambs were slaughtered and they averaged about fifty pounds each. They were lambs dropped this spring, and made a show as good as any Southdowns fed in English pastures.”[xii]

The Harper Brothers were now raising beef that could be described as “genuine British Columbian” and of a quality worth “puffing” about. The following report pokes some fun at the Harpers who were from West Virginia and along with the Jeffries Brothers from Alabama, were Southern sympathizers and had engaged in some privateering shenanigans in Victoria during the recent American Civil War.[xiii]

[i] The Cariboo Sentinel was published in Barkerville for 10 years beginning in 1865.

[ii] Mather, Ken (2018). Trail north, the Okanagan Trail of 1858-68 and its origins in British Columbia and Washington. Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary: Heritage House.

[iii] Cariboo Sentinel, August 25 and September 25, 1869.

[iv] Cariboo Sentinel, August 4, 1869.

[v] Cariboo Sentinel, October 20, 1869.

[vi] Cariboo Sentinel, July 25, 1867.

[vii] Cariboo Sentinel, August 25, 1869.

[viii] Cariboo Sentinel, October 2, 1869.

[ix] Cariboo Sentinel, August 18, 1869.

[x] Cariboo Sentinel, August 11, 14, & 18, 1869.

[xi] Mather, Ken (2018), pp. 229 – 234.

[xii] Cariboo Sentinel, August 14, 1869.

[xiii] See Mather, Ken (2018), pp. 229 – 234.