While many Canadians happily celebrated Canada 150 on 1 July, 2017, Stephen Hume[i] in a Vancouver Sun article reminded us that British Columbia was late to the party and didn’t join Canada until 1871. He mentions that in 1867, “news that a Chinese gardener had driven over from Quesnel with a load of fresh lettuce, onions and radishes” got more press than Confederation in the Cariboo Sentinel published in Barkerville. Not very often do fresh vegetables trump politics in the news! And the involvement of the Chinese in agriculture In British Columbia is often overlooked in BC agricultural history.

Like many others, the Chinese followed the “gold” to British Columbia in 1858 when the gold petered out in California. After the first wave arrived from California, news of the Fraser Canyon Gold Rush and the Cariboo Gold Rush eventually attracted many Chinese from China as well. By the 1850s Barkerville had become the largest city in the British Columbia interior. This gold rush town had a population of approximately 12,000 with nearly 5,000 being Chinese[ii].

By the 1860s, when it became evident that accessible gold through panning had been all been mined, the Chinese began to expand into other labour markets such as mining, salmon canning, agriculture, and logging. Many of the Chinese who came to Canada at this time had left small farming villages in southern China, and they knew how to grow food and crops for sale. At that time, Canada did not exist as a country, and the Chinese had the same full legal rights as the white residents. The Aliens Act of 1861 provided that the aliens, resident for three years within the colony who took the oaths of residence and allegiance, had the rights of British subjects.[iii] Therefore the Chinese the same rights as citizens born there and this included the right to vote and own property[iv]. In many settlements throughout the province, the Chinese turned to farming and grew much of the fresh produce that fed the people who lived there[v]. They were later disenfranchised when British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871, and at various times there were deliberate attempts to prevent them from owning land.

In 1880 the Canadian government began construction of the western portion of the Canadian Pacific Railway. The contractor was unable to secure enough local labour and arranged to bring in 15,700 labourers from China. In 1885, upon completion of the line, the Chinese expected to be paid and shipped back to China. However, this did not happen and many were left destitute, seeking employment wherever they could[vi]. For some it involved returning to what they knew how to do well – produce food.

This large influx of Chinese began to be perceived as a threat and in 1885 the government of Canada struck a Royal Commission on Chinese Immigration[vii]. The commissioners heard evidence such as the testimony of the famous/infamous BC Judge Begbie who said “I do not see how people would get on [exist] here at all without Chinamen” and went on to give several reasons, one being “They are the model [exemplary] market gardeners of the province, and produce the greater part of the vegetables grown here.”[viii] Despite such evidence, the final report recommended moderate legislation to restrict Chinese immigration to Canada and in 1885 the Chinese Immigration Act became law. Among its most controversial aspects was a “Head Tax” of $50 to limit Chinese immigrants from entering the country. By 1903, the Chinese Head Tax reached $500. It is a powerful symbol of racial discrimination and exclusion[ix]. This racially discriminatory law, however, did not stop over 97,000 Chinese from immigrating to Canada between 1885 and 1923 (not all to BC).

Despite racism and discrimination the Chinese became a vital part of the British Columbia landscape. One of their greatest contributions was supplying food – from crop production to sales to cooking[x]. According to Gibb[xi] the anti-Chinese racism sentiment is linked to the emergence of what she calls a parallel food network – one that operates parallel to conventional agriculture (large scale production and distribution systems), that is small scale, hand-cultivation directly marketed for local consumption. This is the domain of Chinese-Canadian market gardeners. It was small scale because major lobbying efforts prevented them from owning land. For example, many public meetings were led by the B.C. Fruit Growers Association to debate whether Chinese should be allowed to acquire land for agriculture between 1917 and 1922.[xii] It was direct marketing because rather than running grocery stores (which were the domain of white shopkeepers), Chinese-Canadian farmers in the early twentieth century tended to sell their wares on foot as vegetable peddlers, using hand-drawn or horse-drawn produce carts. As a result, shopkeepers and vegetable peddlers rarely crossed paths.

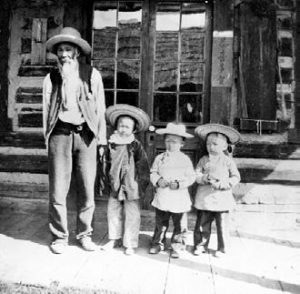

As for those vegetables that arrived in Barkerville in 1867, I’d like to think that they came from Nam Sing Ranch, Quesnel. Chew Nam Sing, who was among the very first and most successful Chinese gold miners in the Cariboo, was born in China’s Kaiping County in 1835 and went to California for the gold rush. He then came north to British Columbia and panned for gold up the Fraser River until he reached the junction of the Quesnel River. During times of high water when it wasn’t possible to work his rocker, Sing cleared a small area and tilled the soil with his gold digging shovel on the west bank of the Quesnel River. He raised a few vegetables for himself and sold the surplus to neighbouring miners using a scow to bring his produce across the river to the townsite. Nam Sing eventually started a large ranch where the Quesnel airport is today and turned to vegetable gardening and ranching for a living.[xiii] He became known as the supplier of fresh food to the restaurants of the gold rush towns in the Cariboo.

According to Heritage BC, the Nam Sing Ranch represents an early and successful agricultural enterprise, developed by one of the province’s first Chinese Canadian families. The historic ranch is valued as one of the earliest examples of commercial market gardening in the province, an agricultural industry developed throughout the province with particular skill and entrepreneurial astuteness by Chinese immigrants.[xv]In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Chinese farmers in BC produced vegetables familiar to European immigrants such as the onions, lettuce and radishes mentioned by Hume and also potatoes, carrots, corn, tomatoes, pickling cucumbers, cabbage, and celery (see the blog posting, Armstrong, BC-Celery City No More). It wasn’t until late in the 20th century that Chinese-Canadian farmers started commercial production of bok choy, gai lan, and other vegetables associated with Chinese culture and cuisine.[xvi]

Chinese Canadians have contributed in many ways to the rich cultural and historical, food mosaic of British Columbia, market gardening being just one example (see the following blog postings for further examples: Wok with Yan and Chinese Fairy Tale Feasts).

References

[i] Hume, S. (2017). Canada 150 Party comes a little early for B.C. http://vancouversun.com/news/local-news/canada-150/canada-150-celebrations-come-a-little-early-for-b-c

[ii] Harris, C. (2011). The resettlement of British Columbia: Essays on colonialism and geographical change. Vancouver, BC:UBC Press.

[iii] Mysteries of Canada. History of the Chinese in Canada. https://www.mysteriesofcanada.com/canada/history-of-the-chinese-in-canada/

[iv] Province of British Columbia (2015). Bamboo shoots: Chinese Canadian legacies in BC. www.openschool.bc.ca/bambooshoots

[v] Yu, J. (2014). The integration of the Chinese market gardens of Southern British Columbia, 1885-1930. https://open.library.ubc.ca/cIRcle/collections/undergraduateresearch/52966/items/1.0228676

[vi] Harris, C. (2011). The Resettlement of British Columbia: Essays on colonialism and geographical change. Vancouver, BC:UBC Press.

[vii] Report of the Royal Commission on Chinese immigration: report and evidence (1985). http://eco.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.14563/3?r=0&s=1

[viii] https://tc2.ca/sourcedocs/history-docs/topics/chinese-canadian-history.html

[ix] Province of British Columbia (2015). Bamboo shoots: Chinese Canadian legacies in BC – Historical Backgrounders

http://www.openschool.bc.ca/bambooshoots/teacher/Bamboo_Shoots_Historical_Backgrounders.pdf

[x] Heritage BC. Chinese Canadian Historic Places: Historical Context Thematic Framework. http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/our-history/historic-places/documents/heritage/chinese-legacy/15380_-_appendix_2_-_chinese_historic_places_context_study.pdf

[xi] Gibb, N. (2011). Parallel alternatives: Chinese-Canadian farmers and the Metro-Vancouver local food movement. Unpublished masters thesis, Burnaby, BC: Simon Fraser University. summit.sfu.ca/system/files/iritems1/11725/etd6663_NGibb.pdf

[xii] Royal BC Museum. Ethnic Agricultural Labour In The Okanagan Valley: 1880s to 1960s. http://royalbcmuseum.bc.ca/exhibits/living-landscapes/thomp-ok/ethnic-agri/contents.html

[xiii] Nam Sing and the gambling loan paid in flour. http://bcgoldrushpress.com/gold-rush-notes/gold-rush-people

[xiv] Source of Photograph: Chinese Canadian Historic Places Statements of Significance for Shortlisted Chinese Canadian Historic Places. http://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/multiculturalism-anti-racism/chinese-legacy-bc/legacy-projects/historical-sites-artifacts/historic-places

[xv] Heritage BC. Chinese Canadian Historic Places Statements of Significance for Shortlisted Chinese Canadian Historic Places. http://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/governments/multiculturalism-anti-racism/chinese-legacy-bc/legacy-projects/historical-sites-artifacts/historic-places

[xvi] Gibb, N. (2011). Parallel Alternatives: Chinese-Canadian Farmers and the Metro-Vancouver Local Food Movement, masters thesis, Burnaby, BC: Simon Fraser University. summit.sfu.ca/system/files/iritems1/11725/etd6663_NGibb.pdf