Learning Canadian Ways

The lives of Catharine Parr Traill (1802-1899) and Alice Ravenhill (1859-1954) spanned two centuries and two continents. They each left successful careers in England to forge new lives in what they thought was the Canadian wilderness. Traill immigrated to Peterborough, Ontario in 1833, and Ravenhill to Shawnigan Lake, BC in 1910. They individually wrote about learning Canadian ways[i], and how to get along in the emerging country of Canada.

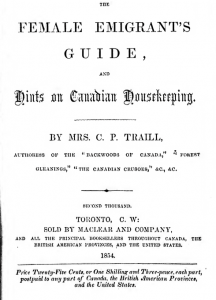

Traill (née Strickland[ii]) began writing in England, and had been published successfully when she moved with her new husband to Peterborough, Ontario around 1832. She continued to write in Canada while raising a large family on very little money. The Female Emigrant’s Guide of 1854 outlined her first three years in Canada, and advised would-be immigrants about what to bring and how to survive in Canada.

McGill-Queen’s University Press republished the book in 2017 as Catharine Parr Traill’s The Female Emigrant’s Guide: Cooking with a Canadian Classic with context and annotations provided by Fiona Lucas and Nathalie Cooke[iii]. In January, 2021 the Culinary Historians of Canada[iv] presented an online lecture by Fiona Lucas showing how Traill survived and enjoyed winter under fierce conditions. These days Traill is recognized as an icon in Canadian literature for her skills in botany and nature and her observations of domestic life[v].

Alice Ravenhill was born into a well-to-do and socially well-placed family with servants and housekeepers to meet her domestic needs. Her upbringing was strict; her father would not allow her to marry the man of her choice or obtain education for employment. In 1890, at the age of thirty, she was finally able to train as a health and hygiene worker at the Royal Sanitary Institute in London. The family fortunes had declined enough to make this feasible and necessary. Ravenhill had a stellar 17-year career as an outreach worker and education. She lectured at the University of London and completed a special report on home economics in America, as well as helping found the American Home Economics Association. In 1910 her sister Edith insisted they should go to Canada to help their brother Horace and his son, Leslie, set up a homestead at Shawnigan Lake on Vancouver Island.

The Ravenhill sisters, both over fifty, had prepared for homesteading through a two month course at Studley College, Warwickshire, but their practical experiences were not useful in the cultural combination of snobbery, classism and rough-and-tumble logging at Shawnigan Lake[vi]. Ravenhill thought they would have been better off learning how to make a wood fire than how to raise cows in the rain forest.

Ravenhill used her British contacts and knowledge of home economics to write six pamphlets for the Women’s Institute [WI]and the British Columbia Department of Agriculture between 1911 and 1917. She did not have the wit and warmth of Catharine Parr Traill, but the information she provided in the pamphlets was valuable. It was not intended for the new immigrant, but rather aimed at improving health and hygiene.

She wrote Labour-saving Devices in the Household [vii](1912) soon after the Ravenhill family was able to move into their spacious Shawnigan Lake home. The 28-page pamphlet included three sections: labour-saving devices of management, experience, and equipment. Items available in the “Old World” and not available in British Columbia such as fire-proof china were frequently mentioned. Ravenhill condemned the feather-duster, viewing it as a dust-scatterer rather than a dust remover. She advocated long-handled dustpans and mechanical labour-saving devices such as carpet-sweepers and a hand-powered vacuum cleaner.

Ravenhill would have appreciated many of Marie Kondo’s[viii] ideas about household efficiency. Housework did not have to be drudgery in the form of patient enduring labour. With efficiency and order it could be seen as a means to an end. Family cooperation of all members was required, not just relying on servant help. Really sharp knives were not an extravagance; mudrooms set up deliberately at the entrance to a home would prevent the intrusion of dirt. Items should be stored at place of first use.

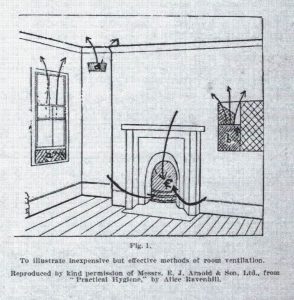

Another WI bulletin, The Art of Right Living[ix], was filled with admonitions for improvement of health and hygiene. Ravenhill suggested an opening be cut in the walls close to the ceilings for better air circulation; that beds be aired daily; that schools be open-air as much as possible; that sleep and all habits be regular. Various neighbours reported Ravenhill’s going around to people’s houses and telling them when and how to change their bedding[x].

Ravenhill convinced the BC Department of Agriculture to publish the Women’s Institute Quarterly magazine and hire her as the editor. This led to confusion over Ravenhill’s views on eugenics (See Appendix).

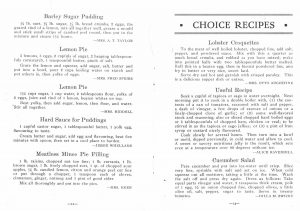

A 1916 Cook Book published by the Kaslo Women’s Institute included a recipe provided by Ravenhill. Entitled “Useful Recipe”, it gives a glimpse into making jellied molds before gelatin became a convenience food and before refrigeration was common. These days, leaving protein foods out at room temperatures for more than two hours between the temperatures of 4 to 60 degrees Celsius breaks food safety rules and runs the risk of serious food-borne illnesses. (It’s the 2-4-60 rule).

A 1916 Cook Book published by the Kaslo Women’s Institute included a recipe provided by Ravenhill. Entitled “Useful Recipe”, it gives a glimpse into making jellied molds before gelatin became a convenience food and before refrigeration was common. These days, leaving protein foods out at room temperatures for more than two hours between the temperatures of 4 to 60 degrees Celsius breaks food safety rules and runs the risk of serious food-borne illnesses. (It’s the 2-4-60 rule).

The recipe doesn’t indicate whether Alice Ravenhill actually knew how to cook, but it does show she wanted to participate.

*****

Thinking about these women’s lives, I wondered how things might have turned out if Catharine Parr Traill had not been plagued by abject poverty and a husband prone to long periods of depression. She still fully embraced life.

Alice Ravenhill had to work continually for her success; many of her character traits such as speaking her mind, and advocating for education at all costs and in all circumstances, worked against her gender. Intuition about human behavior would have benefited her efforts[xi]. “Public health means public wealth” was a deeply held belief of Ravenhill, and it holds true today as much as it did in the early 1900s[xii].

References

[i] The phrase “Canadian Ways” comes from the title of the following article:

Russell, Hilary. “‘Canadian Ways’: An Introduction to Comparative Studies of Housework, Stoves, and Diet in Great Britain and Canada.” Material Culture Review / Revue de La Culture Matérielle 19 (January 1, 1984).

See this link for material culture articles from across Canada: Additional Reading – Nan’s Kitchen https:nanskitchen.ca/resources/additional-reading

[ii] Catharine Parr Traill, was one of six children born to Thomas Strickland and his second wife Elizabeth Homer. Five of the six became writers, echoing the Bronté family. Agnes Strickland wrote extensively on the Queens of England. Two of her siblings also immigrated to Canada, Susanna Moodie and Samuel Strickland. See: https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/strickland-agnes-1796-1874 http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/strickland_catharine_parr_12E.html

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Susanna-Strickland-Moodie

Also: Susanna Moodie’s 1854 book Roughing it in the bush gives a realistic assessment along with sketches and her own poetry. Roughing It in the Bush, Part 1 (Susanna Moodie) [Full AudioBook] – Bing video

[iii] See Sue Carter’s review and interview with Cooke and Lucas. https://quillandquire.com/omni/a-new-edition-of-the-female-emigrants-guide-provides-modern-cooks-with-historic-context/

[iv] Culinary Historians of Canada has a Facebook page and monthly e-newsletter, and online presentations. https://www.culinaryhistorians.ca/wordpress/

[v] See Julie Van Rosendaal’s article. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/books/article-cookbooks-of-the-past-offer-food-for-thought-on-canadas-national/

[vi] See: J. Mason Hurley. Twenty-four colonels on the West Arm Road: Shawnigan Lake in the 1920s. Raincoast Chronicles Fifteen. 1993. pp. 52-61.This article describes the residents on the west side of Shawnigan Lake in the 1920s and 30s, including the Eardly-Wilmots, next door neighbours to the Ravenhills (see also Bosher, pp. 254-259).

[vii] Labour-Saving Devices may be downloaded as a pdf from the Legislative Library, Victoria, BC. The six Ravenhill publications were reprinted in Nova Scotia, and then the type was broken up.

Search Library Catalogue > BC Government Publications> and input title.

[viii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marie_Kondo

I’m pretty sure Ravenhill would have liked Marie Kondo.

[ix] The Art of Right Living is available from the Legislative Library, Victoria, BC. See procedure above for Labour-Saving Devices.

[x] J.F. Bosher, 2010. Imperial Vancouver Island: Who was who, 1850-1950. Xlibris: Author. See p. 610.

[xi] Gwen Cash, “Handicrafts of B.C. Indians find English guardian angel”. Vancouver Daily Province, 29 March, 1941, p. 2 Magazine section.

Cash’s article describes Ravenhill’s personality, as an “English Guardian Angel” in her work with Indigenous handicrafts, who could be caustic at times and didn’t suffer fools lightly.

[xii] A. Ravenhill, The teaching of hygiene, American Kitchen Magazine, Vol. 17, No. 3, 184-189. Cited in M.G. Smith, Alice Ravenhill: International Pioneer in Home Economics, Illinois Teacher, Vo. 22, No. 1, September/October, 1989, p. 12. Ravenhill used this expression in various writings.

Appendix: Alice Ravenhill and Eugenics

A number of years ago, I used “as cited in” as a reference to Alice Ravenhill’s views of the Empire, as expressed in the WI Quarterly in 1915. The context was a quotation from Angus McLaren, Our own master race: Eugenics in Canada 1885-1945, published in 1990.

Alice Ravenhill, prior to World War One, was British Columbia’s most noted authority on the subject. An expert in household science and child hygiene, Ravenhill had arrived in Canada in 1910 after having played an active role in English eugenic circles. In British Columbia, both as a popular public speaker and as editor of the Women’s Institute Quarterly, she spread the eugenic message. Perusers of the Quarterly in 1915 found among the recipes for bread and pickles and advice on the dressing of poultry and the canning of strawberries the bellicose declaration:

The next enemies of the Empire will need to be even better prepared than the Germans, for the women are leaving nothing undone. Their soldiers are to be well-born, for they are making a study of eugenics. They are to be well-bred, for they have their domestic science and they are solving moral problems (McLaren, 1990, p. 26).

I quoted the above almost directly (as cited in McLaren) and it read like Ravenhill was a hardened eugenicist. When I finally located the original Women’s Institute Quarterly (1915), I saw that the quote “The next enemies….etc.” was not made by Ravenhill but by a Kootenay WI Branch. Yet the McLaren quote makes her look like a raving eugenicist. That is too complicated a subject to dismiss in one sentence. This reinforced a pale, inadequate image of Ravenhill persisting to this day as a racist – yet her later work with Indigenous arts and crafts showed in many ways the shallowness of the description, and the ways in which she walked back her previous opinion, much the same as Tommy Douglas and other notable Canadians who were eugenicists at one point, and changed their minds.