Early Contact Foods of BC

In this post I want to share a few gleanings about BC food history from some general history books of the 18th and 19th centuries. A story emerges from this era of explorers and traders bringing to the Northwest seeds and plants from their home country, of them being introduced to indigenous foods of the First Nations people they meet, and a melding of different food traditions over time. The indigenous plants were being nurtured, transplanted, and pruned by the First Nations women and a kind of agricultural practice already existed. Carol Martin[i] was surprised to find that “few general histories of Canada mention gardening at all – an activity that has been important, even essential, to our survival.” I am less surprised because much of our history is indeed “his-story” and unfortunately while Martin’s book on gardening attempts to be broadly focused it tells us more about Eastern Canadian gardening practices than those of the West Coast.

I turned first to a book that had languished too long on my bookshelf[ii] because I did want to know more about Spanish exploration on the West Coast. Tovell focuses on Bodega Y Quadra’s explorations from 1775 to 1793. The Spaniards kept a naval base at San Blas Mexico and from it supplied the Spanish missions along the Camino Real in Alta California that extended from present day San Diego to San Francisco. From it, they also launched their explorations of the west coast of BC. Exploration was along the west coast of Vancouver Island and for a short while they occupied a base at Nootka. Their desire was to establish a mission similar to those in Alta California where Catholicism, settlements and farming could be introduced. But Nootka was not conducive to this because it lacked the topsoil needed for farming and gardening. A settlement was developed at Neah Bay, on the Northern tip of Puget Sound. There, they introduced livestock and vegetable seedlings brought from San Blas.

It appears though that a productive settlement of sorts must have developed eventually at Nootka because in 1792, Bodega spent the summer there waiting for Capt. George Vancouver to arrive so together they could negotiate face to face the Nootka agreement, a settlement between Spain and Britain. Playing this diplomatic role, Bodega took very seriously his role as host and entertainer of visiting ships and especially Vancouver and crew while they were in Nootka harbour. In Mexico City, before leaving for San Blas and Nootka in 1792, Bodega stocked up with foods he deemed essential to being a “genial” host: “barrels of brandy, table wines, cases of bottled vintage wines, wine skins of cider and beer, Flemish (fine) lard and hams; pickled greens, vegetables in oil, Castillian vinegar and olives; parboiled fowl and marinated meats; flours, cookies, chocolate, coffee, sugar, and sweetmeats.”[iii] In addition he stocked up on cattle, hens, cheese, preserves, dried fruit, and other delicacies. Bodega entertained lavishly and served on silver plates.

In addition to all the imported foods, he “also supplied visiting ships with fresh produce while they were in port. Every day each ship in port was sent hot rolls from the oven, vegetables from the gardens and fresh milk from the goats and cows.”[iv] With this bounty of fresh foods available in Nootka, one can only assume that a garden as well as domesticated animals were introduced and had begun to thrive by 1792. This generosity extended also to the First Nations people, the Mowachaht chief Maquinna and his people who occupied the land and verbally agreed to let the Spaniards reside there for a length of time. Exchanges of food and entertainment with the First Nations occurred under Bodega’s watch.

Frances Barkley was newly married at the age of 18 when she joined her husband Charles Barkley on board the Imperial Eagle in 1787 and sailed to the coast of what would later become British Columbia, trading for sea otter pelts to be conveyed to and sold in China. Her journal provides a few insights into how they provided food for themselves. They carried on the upper deck of the ship cattle, pigs, chickens and turkeys to supply dairy and meat for the crew. In 1792, Frances and Charles Barkley were on the north coast in Admiralty Bay, the territory of the Tlingit. Frances describes how the First Nation men fished and traded their fish to those on the ship while the women frequently came with “very nice berries of different kinds…wild strawberries….blackberries…raspberries.”[v] Frances wrote that she and Charles were allowed to go on shore where they saw “cultivation” happening. Oats, peas and strawberries had been planted and were thriving. Frances noted in her journal that frequently, they and other voyaging explorers planted crops in remote places expecting that future travelers would find and benefit from the food. When the Barkleys returned a second time to Hawaii they found watermelons growing from seeds planted earlier by Captain Rogers. The turkey cock and hen they had left with a Chief five years earlier had reproduced, giving many off spring that were gifted to other chiefs.[vi]

The traders and explorers were altering the available foods as they made contact with the land and indigenous people. Like guerilla gardeners of today, they carried seeds and planted them expecting that they or other travelers might return someday to benefit from the crop. It was late in the 1700s when the Spaniards began to include naturalists or botanists on their voyages but the British had earlier realized their importance in gathering and studying indigenous plants and in many cases carrying some back to their land of origin.

In 1825, David Douglas (for whom the Douglas Fir is named) left England sent by the Horticulture Society to America to investigate fruit and forest trees and to search for plants that might find a place in English gardens. Because Douglas had spent considerable time apprenticing in kitchen gardens and gardening in England, he was likely more observant of the plants that First Nations people grew and ate. This was reflected in the notes he made about the plants grown and eaten.[vii]

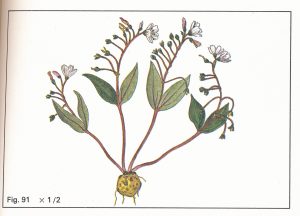

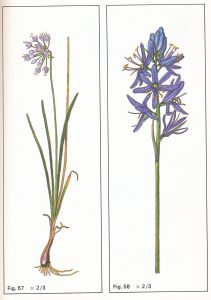

Douglas began his explorations venturing out from the ship docked in the Columbia River. He observed the First Nations children gathering young horsetail stems and eating them either raw or boiled. Venturing up river, with First Nations companions, he ate wild raspberry shoots and dined on sturgeon and salmon caught in the river. Their destination was Fort Vancouver where cattle, horses and pigs were kept and a large garden of potatoes and peas was being planted. He watched the First Nations women of the area use pointed digging sticks to unearth the corms of camas lilies and bake them in earth ovens.[viii]

In 1826, Douglas ventured up the Columbia into Fort Colville and Spokane House areas. At Spokane House he enjoyed a meal of camas, bitterroot and cakes of black tree lichen. To make the cakes, the women gathered the black lichen that grew on trees, removed any twigs and soaked it in water. When the lichen was soft, it was arranged in an earth oven, layered on stones and protected from below and above with layers of grass and dead leaves. After the lichen baked all night, it was removed from the coals and now a sticky goo, it was shaped into cakes while still warm. [ix] Douglas came to appreciate a purplish wild onion that grew abundantly along the riverbanks and watched the First Nations women dig desert parsley that grew in swampy areas. He relied heavily on a variety of wild meat: fish, grouse, bear, deer, bighorn sheep, ducks, geese, bison; and wild berries: huckleberries, yellow currants, blackberries. Douglas’ explorations took him up the Columbia and over the Rocky Mountains across the prairies and as far as Fort Garry. On an 1833 trip he explored more of the BC Interior and journeyed up the Thompson and Fraser Rivers. Nisbet speculated that he surely would have tasted “Indian potatoes” or the bulbs of Spring beauty that was commonly eaten by the First Nations in the Thompson Okanagan areas. [x]

[i] Martin, Carol (2000). A history of Canadian gardening. Toronto: McArthur & Company, p. x.

[ii] Tovell, Freeman M. (2008). At the far reaches of Empire, the life of Juan Francisco de la Bodega Y Quadra. Vancouver: UBC Press.

[iii] Janet Fireman in Tovell, p. 225.

[iv] Tovell, p. 227

[v] Hill, Beth with Cathy Converse ( 2003). The remarkable world of Frances Barkley, 1769 – 1845. Victoria: Touchwood, p. 133.

[vi] Beth Hill with Cathy Converse, p. 144.

[vii] Nisbet, Jack (2009). The collector, David Douglas and the natural history of the Northwest. Seattle: Sasquatch Books.

[viii] Nisbet, p. 45.

[ix] Nisbet, p. 84.

[x] Nisbet, p. 220.

Photo source:

Porsild, A.E. (1974). Rocky Mountain wild flowers. Ottawa: National Museums of Canada.