Okanagan Bitterroot

This week as part of RespectFEST[i] in Vernon BC, I listened to Mollie Bono, an Okanagan elder, speak on the History of the First People: Pre-Contact. She spoke about the traditions of everyday life among the Okanagans, especially from a woman’s perspective and their relation to the land and their food sources. She mentioned the importance of bitterroot, telling us that families in the Vernon area used to travel as far south as Penticton in the spring to dig this plant using a curved wooden type of hoe. While I have lived in this area for some time, I have not seen bitterroot growing. This left me curious to know more.

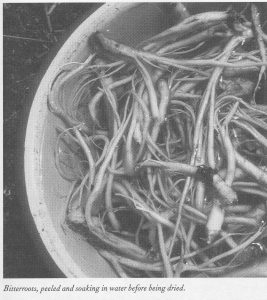

The First Nation name for what has come to be known as Bitterroot (Lewisia rediviva), is Spatlum or Spaetlum[ii]. It grows in thin gravelly soil at low elevations in open dry, rocky areas.[iii] It is a small plant about two inches high, that grows in early spring from fleshy taproots and sprouts succulent-type leaves that tend to dry and shrivel when the flowers bloom. The flowers are usually 4 to 6 cm across and look like bright pink water lilies (see photo 1). Bitterroot was highly prized throughout the inland northwest as both a traditional food for First Nations and an item for trade. The fleshy roots were gathered, peeled to remove the bitter skin, boiled, roasted, or dried for winter storage. In the Okanagan system of classifying living beings, bitterroot is the “chief” of roots. For the Nlaka’pmx, bitterroot was sacred and the plants themselves were once human. Bitterroot often grows entwined in pairs, and for this reason Nlaka’pmx couples planning to marry and wishing to stay together forever looked for a bitterroot pair to place under their pillow as a symbolic guiding spirit for their own intimacy.[iv]

Nancy Turner wrote that the Nlaka’pmx women around Spences Bridge and Ashcroft harvested bitterroot selectively and replanted parts of the root to ensure that the plants would re-grow.[v] They also transplanted it to other areas as a way of extending the region of growth and cultivated around the plant to encourage more robust growth. During the last 100 years many plants have been killed by overgrazing cattle, soil compaction, and industrial use of the land. As a result, bitterroot has become rare and endangered in many regions of BC where it used to be abundant.

A recipe for bitterroot credited to John McIntyre of the Fraser Canyon Tribal Council combines 2 cups of dried saskatoons with 4 tablespoons of dried bitterroot and sugar to taste. Put all in a pot and add water. Boil to consistency of applesauce. Some people add flour as a thickener. Eat hot or cold.[vi]

Further ways of eating, courtesy of Joyce Sam and Laura Washington in the same publication, state that bitterroot can be mixed with fish eggs, saskatoons and flour. Cook to a custard or pudding consistency. If eaten as a main meal, salt would be added; if eaten as a dessert, sugar would be added.

References:

[i] https://respectfest2017.com/

[ii] Scotter, George W. & Halle Flygare (2007). Wildflowers of the Rocky Mountains. North Vancouver: Whitecap Books.

[iii] Durance, Eva (2009). Cultivating the wild. Delta, BC: Nature Guides BC.

[iv] Turner, Nancy J. (2005). The earth’s blanket. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre.

[v] Turner, Nancy J. (2005). The earth’s blanket. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre.

[vi] https://www.for.gov.bc.ca/rsi/fnb/bitter-root.pdf

Photo sources

Photo 1: Clark, Lewis J. (1973). Wild flowers of British Columbia. Sidney, BC: Gray’s Publishing, p. 135.

Photo 2: Turner, Nancy J. (2005). The earth’s blanket. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, p. 31.