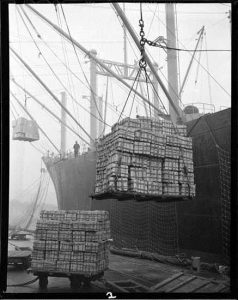

When I was growing up in the 1950s in north western British Columbia I can distinctly remember watching the newspaper at this time of year for an announcement that Japanese Mandarin Oranges (Satsuma) had arrived in Vancouver. The article often made front page news and was accompanied by a picture similar to this one taken in 1949.

Christmas mandarin oranges being unloaded from the ship, S.S. American Mail. (Philip Timms photo, Vancouver Public Library, 5222).

Christmas mandarin oranges being unloaded from the ship, S.S. American Mail. (Philip Timms photo, Vancouver Public Library, 5222).

Once the announcement came in the provincial newspaper (that usually arrived in our community two days after it was published) I knew my favourite oranges would arrive within a week. At that time they were a special treat, unlike today when mandarin oranges are available pretty much all year round. You could only get Japanese Mandarin oranges in December and one of these oranges was always in the toe of my Christmas stocking. According to some sources, the first ship to arrive was greeted with a festival that included Santa Claus and Japanese dancers[i].

Japanese Mandarin oranges have a long history in British Columbia. The tradition of sharing these oranges during holiday season dates back to the first Japanese immigrants who came to Canada in the late 1800s. It was customary for them to receive packages of Satsuma oranges from their families in Japan to celebrate the New Year. They shared the oranges with their neighbours and friends and thus a new Canadian tradition was born[ii].

Access to Japanese Mandarin oranges was facilitated by the five Oppenheimer brothers (David, Charles, Godfrey, Isaac, Meyer) who immigrated to North America in 1848 to escape the persecution of German Jews in Bavaria. They began a wholesale grocery business in New Orleans, Louisiana and then relocated to Sacramento, California at the height of the gold rush. Here they became merchants catering to the miners rather than prospecting for gold themselves. Meyer launched a successful business in Sacramento, while David and his wife ran a hotel in the nearby town of Columbia. After the California gold fields were played out, many of the miners headed north to British Columbia to take part in the Fraser River gold rush. In 1858 three of the brothers followed to supply the miners’ needs. Charles arrived first and established a trading business known as Charles Oppenheimer and Co. The family partnership expanded when David and Isaac Oppenheimer opened a general store in Yale, British Columbia, to outfit prospectors that soon expanded to other mining camps, such as Fort Hope and Lytton. Shortly thereafter the three brothers formed Oppenheimer Bros. and Company, a wholesale grocery company to supply their stores. As the gold rush moved north, the brothers opened a store in Barkerville in 1862. When the gold ran out, the brothers chose to stay in British Columbia. David and Isaac settled in Vancouver in 1885, where they established a wholesale warehouse in the city’s first brick building. The Oppenheimer Group (Oppy) continues to thrive to this day specializing in fresh fruit and vegetables.

In 1884 the Oppenheimer firm formed an alliance with the Japan Fruit Growers Cooperative and began importing Japanese Mandarin oranges packed in wooden boxes with each piece of fruit wrapped in green tissue for the Christmas season.

Once the oranges arrived in Vancouver, they were transported by truck and train throughout BC and across Canada. After the oranges had all been eaten, the wooden crates were converted to a myriad of other useful items. I remember using one as a doll bed for my Barbara Anne Scott doll. In our household one was turned upside down and used as a step stool for children to reach sinks and counter tops. Eventually, the wooden boxes were replaced by more cost efficient cardboard containers, though many people remember the well constructed and functional wooden crates almost as fondly as the oranges themselves.

Once the oranges arrived in Vancouver, they were transported by truck and train throughout BC and across Canada. After the oranges had all been eaten, the wooden crates were converted to a myriad of other useful items. I remember using one as a doll bed for my Barbara Anne Scott doll. In our household one was turned upside down and used as a step stool for children to reach sinks and counter tops. Eventually, the wooden boxes were replaced by more cost efficient cardboard containers, though many people remember the well constructed and functional wooden crates almost as fondly as the oranges themselves.

During World War II the longstanding ties with Japanese exporters had to be severed and mandarin oranges went missing from Christmas for a few seasons. When trade resumed after the war, the firm quickly re-established its relationship with the Japanese growers. In the days before refrigerated trains, Oppenheimer commissioned special trains, the boxcars painted orange, to take the oranges straight from the ships to Eastern Canada, where the residents knew the holiday oranges had arrived by the sight of the brightly colored railcars[iii].

In 1977 Canadian Pacific Railway created a special boxcar painted similar to the model shown as the Mandarin Orange Express, to lead the train that was transporting the years’ Mandarin oranges for the Christmas season to Eastern Canada. This boxcar, which was placed right behind the engine, was used to advertise the largest shipment ever handled by CP Rail. The CP Rail News of 28 January, 1978 reported that “more than nine million oranges, filling 60 temperature-controlled insulated box cars made up this special ‘Mandarin Express.’”[iv]

How the oranges ended up in the toes of Christmas stockings is another tradition that has no clear explanation. The most common one connects it with St. Nicholas, as described in ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas (Clement Clarke Moore, 1922), “the stockings were hung by the chimney with care in hope that St. Nicholas soon would be there”. According to the St. Nicholas Center the original Nicholas was a fourth century Christian Bishop in what is now southern Turkey. He was known for helping the poor, and when he learned of a poor man who didn’t have money for his three daughters’ dowries, St. Nicholas traveled to the house, and tossed three sacks of gold down the chimney for each of the girls to be able to get married. The gold happened to land in each of the girls’ stockings which were hanging by the fire to dry. The gold Nicholas threw to provide the dowry money is often shown as gold balls and oranges are said to symbolize the gold balls[v]. Perhaps an orange in the toe of a stocking became more common in the Great Depression of the 1930s, when money was tight and an orange in a stocking at Christmas was a special treat. Those oranges would most likely be the Japanese Mandarins that came across the country by train.

Walt Breeden, the current vice-president of sales at The Oppenheimer Group, calls Japanese Mandarin oranges “the Cadillac” of brands[vi]. “The Japanese [orange] has a nice balance between sweet and tart”. One food puts us in touch with so much history, both sweet and tart – persecution in Eastern Europe; the immigrant experience; the BC gold rush; the history of the CPR; the treatment of Japanese Canadians during the war; international transportation and trade; how tradition influences the food we eat; and the mingling of cultures in our multicultural society.

References:

[i] Mandarin Orange Madness (2014)

http://luvoinc.com/blog/mandarin-orange-madness/#e6TdwaZbWzJKpFkm.99

Marion, P. (2014). Oranges at Christmas. http://www.richardhowe.com/2014/12/06/oranges-at-christmas-5/comment-page-1/

[ii] BC Agriculture in the Classroom. Mandarin oranges. www.aitc.ca/bc/uploads/sfvnp/MANDARIN%20ORANGES%206.pdf

[iii] International Directory of Company Histories (2006). The Oppenheimer Group. http://www.encyclopedia.com/books/politics-and-business-magazines/oppenheimer-group

The Oppenheimer Group. https://www.oppy.com/who-we-are/company-history

Reference For Business. The Oppenheimer Group – Company Profile, Information, Business Description, History, Background Information on The Oppenheimer Group. http://www.referenceforbusiness.com/history2/81/The-Oppenheimer-Group.html#ixzz4SN5ZLmJI

[iv] CP RAIL NEWS, Jan. 18/78 cited in The Business Car section of Canadian Rail (1978, March).

[v] St. Nicholas Center. http://www.stnicholascenter.org/pages/usa-christmas-customs/

[vi] Proctor, J. (2015, Dec. 1). Mandarin Idol: Which orange is worthy of citrus stardom? CBC News. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/mandarin-idol-which-orange-is-worthy-of-citrus-stardom-1.3344421