Recipes for Victory

Every November our thoughts turn to Remembrance Day and the role food has played during wartime over the years.

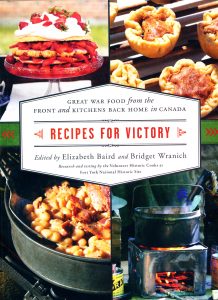

In 2018, Elizabeth Baird and Bridget Wranich released Recipes for Victory, a collection of recipes and research papers that were part of a 2014 Great War Food Symposium organized at the Fort York National Historic Site in Toronto. Baird and Wranich document the many ways the home front (mainly women) were mobilized in wartime to support food production and expand food supplies at home in support of the war effort. They dedicated the book to:

…all Canadians whose lives were changed irrevocably by the global conflict. From those who served on the fields of battle to those who supported war efforts in home-front kitchens across the nation, they shall be remembered. May future generations continue to connect to the men and women of that era through the comfort and sharing of food.

When Britain declared war on Germany in August 1914, Canada was automatically drawn into the conflict. Canada’s first response was with food. The federal government committed one million bags of flour to Britain. Quebec sent four million pounds of cheese and British Columbia 1.25 million tins of salmon (Reeves, 2018). These symbolic acts to meet the gastronomic needs of Britain were an essential part of the war response as much as sending munitions and men. The challenge on the home front was how to increase the availability of food overseas and the responses came through food production, consumption, conservation and regulation. Food was also sent directly to troops and was a common tool in fund raising for the war effort (Reeves, 2018).

The federal government took steps to increase agriculture production that included providing tractors to farmers, encouraging young farmers to remain in production rather than enlisting, and encouraging pork production for Britain. Urban residents were encouraged to plant gardens to make their food dollar go farther and decrease domestic demand for food. Individuals and community organizations took up the challenge to support home gardens.

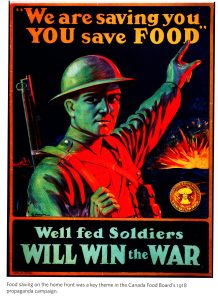

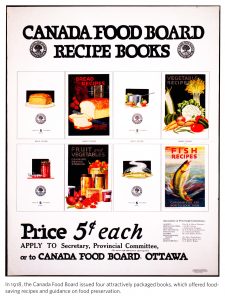

By 1917, the federal government realized that the public appeals were inadequate in increasing food production. They appointed a Food Controller for Canada and in 1918 created the Canada Food Board. Both these offices were responsible for stronger promotion and propaganda strategies. Posters, booklets encouraging food substitutes, thrift, and preservation, and a newspaper column “War Menus” carried in newspapers across Canada were strategies promoted by the Food Board. Canada did not have food rationing in World War I but by 1918 food regulations did come into play. It became illegal to make candies or put icing on cakes, biscuits and pastries at home and to hold more than 15 days’ supply of sugar and flour. The penalty in both cases was a fine of $100 to $1,000 and/or three months’ imprisonment. A second regulation required bakers to label bread that contained wheat substitutes with “Victory Bread” labels (Reeves, 2018).

Food gifts from Canadian families to soldiers in Europe were welcome and frequent. Treats were shared among comrades and links to community and family back home solidified. Many women’s clubs in Canada produced fundraising cook books and some communities sent gifts each Christmas to their soldiers overseas.

Reeves notes that there is little evidence that the changes in daily diets that were encouraged during the war continued afterwards. However he notes that encouraging conservation, preservation, local eating and eating more vegetables and less meat resonates with the kind of healthy diets advocated in today’s environmental crises. What’s old is new again!

References

Baird, Elizabeth & Wranich, Bridget (Eds.) (2018). Recipes for victory. Vancouver: Whitecap Books.

Reeves, Wayne (2018). Delectable weapons: Food, Drink and Canadians During the First World War. In E. Baird & B. Wranich (Eds.). Recipes for victory (pp. 10 – 31). Vancouver: Whitecap Books.